Michigan Relics: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

===The University of Michigan=== | ===The University of Michigan=== | ||

In 1898, the University of Michigan was presented with the opportunity to purchase a collection of the relics for the University museum. The batch that was offered had travelled the country as an exhibit, advertised as "The Finest Collection of Pre-Historic Relics Ever Exhibited in the United States." The original price asked was one thousand dollars which was quickly lowered to one hundred dollars. The University had been involved in the matter several years prior, in 1892, when Professor Frank Kelsey evaluated the Scotford finds as archaeological forgeries. The curator of the museum declined the offer to purchase the material, which was still deemed fraudulent and denounced by academics. However, the University obliged when asked to store the collection. In an effort to keep the bogus relics off the market, the University of Michigan stored the crates for several decades with the understanding that the owner would eventually retrieve the fake artifacts - they never did. | In 1898, the University of Michigan was presented with the opportunity to purchase a collection of the relics for the University museum. The batch that was offered had travelled the country as an exhibit, advertised as "The Finest Collection of Pre-Historic Relics Ever Exhibited in the United States." The original price asked was one thousand dollars which was quickly lowered to one hundred dollars. The University had been involved in the matter several years prior, in 1892, when Professor Frank Kelsey evaluated the Scotford finds as archaeological forgeries. The curator of the museum declined the offer to purchase the material, which was still deemed fraudulent and denounced by academics. However, the University obliged when asked to store the collection. In an effort to keep the bogus relics off the market, the University of Michigan stored the crates for several decades with the understanding that the owner would eventually retrieve the fake artifacts - they never did.<ref>Kelsey, Francis W., "Archaeological Forgeries from Michigan." ''American Anthropologist'', New Series, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Jan. - Mar., 1908), 48-59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/659777.pdf</ref> | ||

The pieces in this collection of the Michigan Relics were different than the earlier pieces that had been found and evaluated. The clay was baked more thoroughly and the craftsmanship of the pieces was better all around. The academic assessments of the relics in the early 1890s had provided a framework for the pieces to be made more convincingly. Though the Michigan Relics were deemed fraudulent by countless academics throughout the decade, Scotford persisted in promoting and selling the pieces that he continued to uncover, seemingly endlessly, throughout the state. | The pieces in this collection of the Michigan Relics were different than the earlier pieces that had been found and evaluated. The clay was baked more thoroughly and the craftsmanship of the pieces was better all around. The academic assessments of the relics in the early 1890s had provided a framework for the pieces to be made more convincingly.<ref>Kelsey, Francis W., "Archaeological Forgeries from Michigan." ''American Anthropologist'', New Series, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Jan. - Mar., 1908), 48-59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/659777.pdf</ref> Though the Michigan Relics were deemed fraudulent by countless academics throughout the decade, Scotford persisted in promoting and selling the pieces that he continued to uncover, seemingly endlessly, throughout the state. | ||

==The Relics in the Early Twentieth Century== | ==The Relics in the Early Twentieth Century== | ||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

In 1960, while proselytizing in South Bend, Indiana at the University of Notre Dame, two missionaries of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints came across James Savage's collection of the Michigan Relics. They wrote back to Milton R. Hunter, president of the New World Archaeological Foundation, the research institute of the Mormon Church. Hunter's research involved the historicity of the Book of Mormon through archaeological evidence. In 1962, Hunter visited Notre Dame to view the Savage collection, which the University subsequently gave him. Following his success at Notre Dame, Hunter contacted the son of Daniel Soper, Ellis Clarke Soper, who had inherited his father's collection. Ellis Soper originally lent Hunter a few pieces, but eventually gave him the entire collection. Hunter's diligence in his research and collection brought most of the Michigan Relics together.<ref>Ashurst-McGee, Mark. "Mormonism's Encounter with the Michigan Relics," ''BYU Studies,'' vol. 40, no. 3 (2001), 196. https://byustudies.byu.edu/content/mormonisms-encounter-with-michigan-relics</ref> | In 1960, while proselytizing in South Bend, Indiana at the University of Notre Dame, two missionaries of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints came across James Savage's collection of the Michigan Relics. They wrote back to Milton R. Hunter, president of the New World Archaeological Foundation, the research institute of the Mormon Church. Hunter's research involved the historicity of the Book of Mormon through archaeological evidence. In 1962, Hunter visited Notre Dame to view the Savage collection, which the University subsequently gave him. Following his success at Notre Dame, Hunter contacted the son of Daniel Soper, Ellis Clarke Soper, who had inherited his father's collection. Ellis Soper originally lent Hunter a few pieces, but eventually gave him the entire collection. Hunter's diligence in his research and collection brought most of the Michigan Relics together.<ref>Ashurst-McGee, Mark. "Mormonism's Encounter with the Michigan Relics," ''BYU Studies,'' vol. 40, no. 3 (2001), 196. https://byustudies.byu.edu/content/mormonisms-encounter-with-michigan-relics</ref> | ||

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints invests greatly in attempts to prove the historical legitimacy of the Book of Mormon, often through archaeology. Hunter spent many years researching the Michigan Relics in attempts to prove their legitimacy. While Rudolph Etzenhouser had attempted to make this connection earlier in the twentieth century, Hunter was more committed to the cause and spent the rest of his life working at it. Hunter was, however, among the only interested parties in the Mormon Church. Most other officials, including president David McKay, trusted prior assessments and evaluations that deemed them archaeological forgeries. Hunter persisted, just as Scotford and Soper did, in ignoring basic facts about the Michigan Relics and published extensively on them. Eventually Hunter connected the "Michigan Mound Builders" who made the relics to the Nephites from the Book of Mormon. This conclusion perpetuated the | The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints invests greatly in attempts to prove the historical legitimacy of the Book of Mormon, often through archaeology. Hunter spent many years researching the Michigan Relics in attempts to prove their legitimacy. While Rudolph Etzenhouser had attempted to make this connection earlier in the twentieth century, Hunter was more committed to the cause and spent the rest of his life working at it. Hunter was, however, among the only interested parties in the Mormon Church. Most other officials, including president David McKay, trusted prior assessments and evaluations that deemed them archaeological forgeries. Hunter persisted, just as Scotford and Soper did, in ignoring basic facts about the Michigan Relics and published extensively on them. Eventually Hunter connected the "Michigan Mound Builders" who made the relics to the Nephites from the Book of Mormon. This conclusion perpetuated the mound builder myth that already existed in pseudoarchaeology. Before his death in 1975, Hunter left his vast collection of Michigan Relics to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.<ref>Ashurst-McGee, Mark. "Mormonism's Encounter with the Michigan Relics," BYU Studies, vol. 40, no. 3 (2001), 196-197. https://byustudies.byu.edu/content/mormonisms-encounter-with-michigan-relics</ref> | ||

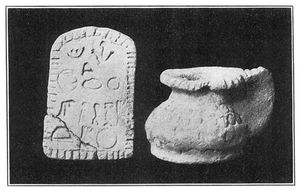

[[File:Relics2.JPG|thumb|300px|left|Michigan Relics, clay tablet and cup. <ref>Kelsey, Francis W., "Archaeological Forgeries from Michigan." ''American Anthropologist'', New Series, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Jan. - Mar., 1908), 50. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/659777.pdf</ref>]] | [[File:Relics2.JPG|thumb|300px|left|Michigan Relics, clay tablet and cup. <ref>Kelsey, Francis W., "Archaeological Forgeries from Michigan." ''American Anthropologist'', New Series, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Jan. - Mar., 1908), 50. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/659777.pdf</ref>]] | ||

Latest revision as of 21:58, 1 December 2017

By Jacob McCormick

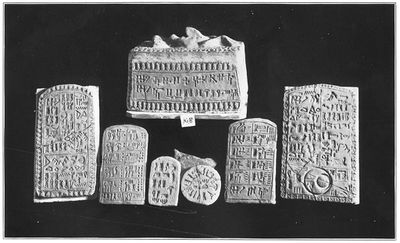

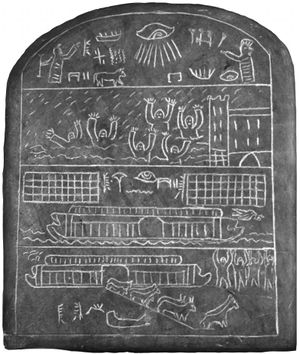

The Michigan Relics (also known as the Scotford Frauds, the Soper Frauds, or the Scotford-Soper Frauds) are a large grouping of pseudoarchaeological prehistoric artifacts "discovered" throughout the state of Michigan in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Many of the relics were inscribed with fraudulent hieroglyphs and cuneiform and were originally believed to be proof of pre-Columbian contact with the Americas. The Michigan Relics are considered, for many reasons, to be one of the most elaborate and extensive archaeological hoaxes ever perpetrated in American history.[2]

The Relics in the 1890s

The first discovery of the relics in Michigan occurred in October 1890 when James O. Scotford found a small clay cup while digging post holes in a field in Wyman, Montcalm County, Michigan. Scotford was a well-known digger and sign painter in the area of Wyman. Shortly after that initial discovery in Wyman, many other more elaborate discoveries were made in a three or four mile diameter around the village. Most of the artifacts were authenticated by the prominent locals who witnessed their discovery. Scores of "remarkable objects" were unearthed anywhere from one to four feet into the surface undulations and mounds. [4] Among the objects uncovered were small caskets, tablets, ornaments, weapons, tools, smoking pipes, and pottery vessels made of copper and baked and unbaked clay of varying colors. Within the first year of Scotford's initial discovery a syndicate was formed in Montcalm County of interested parties. The syndicate purchased many of the artifacts and attempted to exploit the finds financially for the region.[5]

First Debunked in 1891

Scotford's "Michigan Relics" were quickly debunked by academics who found problems with the discoveries. Professor F.W. Putnam, curator of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University from 1874 to 1909, was sent photographs of the discoveries. Professor Alfred Emerson, an archaeologist at Lake Forest College (who later moved to Cornell University), reviewed the "relics" in June 1891. Following his visit, Emerson wrote "The articles were bad enough in the photograph... an examination proved them to be humbugs of the first water." Emerson's evaluation of the objects was swift and decisive, the Michigan Relics were archaeological forgeries. One scholar called them "remarkable only for their clumsy character."[6]

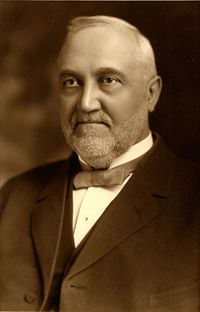

In 1892, Professor Francis W. Kelsey, professor of Latin and Literature at the University of Michigan, along with Professor Morris Jastrow, Jr., librarian and professor of Semitic languages at the University of Pennsylvania, joined Emerson in calling the Michigan Relics frauds. Kelsey and Jastrow primarily evaluated the linguistics on the objects, calling the relics a "horrible mixture" of jumbled ancient scripts. Both professors agreed that the finds were fraudulent and were produced by someone with no knowledge of linguistics or the ancient languages they attempted to replicate on the objects.[7] Even with no archaeological training, Kelsey concurred with Emerson's evaluation of the flaws of the objects, he outlined some specific observations in his publication on the topic:

- The hieroglyphs were stamped cuneiform characters in random order.

- The figures on some of the discoveries included lions with no tails, an omission which would not have occurred by "primitive" artists.

- The clay items were dried on a machine-sawed board.

- The objects disintegrated in water, indicating that they could not have been buried in the ground for very long.[9]

Despite the Michigan Relics being thoroughly debunked by several academics across the United States, Scotford persisted in promoting the artifacts. With the consensus in the academic community on the relics, the syndicate in Montcalm County that was formed in support of the relics was disbanded. In 1893, Walter Wyman, head archaeologist of the Chicago World's Fair, turned away Scotford's submission of a stone casket to the fair and concurred with prior assessments that the Michigan Relics were fraudulent.[10]

The University of Michigan

In 1898, the University of Michigan was presented with the opportunity to purchase a collection of the relics for the University museum. The batch that was offered had travelled the country as an exhibit, advertised as "The Finest Collection of Pre-Historic Relics Ever Exhibited in the United States." The original price asked was one thousand dollars which was quickly lowered to one hundred dollars. The University had been involved in the matter several years prior, in 1892, when Professor Frank Kelsey evaluated the Scotford finds as archaeological forgeries. The curator of the museum declined the offer to purchase the material, which was still deemed fraudulent and denounced by academics. However, the University obliged when asked to store the collection. In an effort to keep the bogus relics off the market, the University of Michigan stored the crates for several decades with the understanding that the owner would eventually retrieve the fake artifacts - they never did.[11]

The pieces in this collection of the Michigan Relics were different than the earlier pieces that had been found and evaluated. The clay was baked more thoroughly and the craftsmanship of the pieces was better all around. The academic assessments of the relics in the early 1890s had provided a framework for the pieces to be made more convincingly.[12] Though the Michigan Relics were deemed fraudulent by countless academics throughout the decade, Scotford persisted in promoting and selling the pieces that he continued to uncover, seemingly endlessly, throughout the state.

The Relics in the Early Twentieth Century

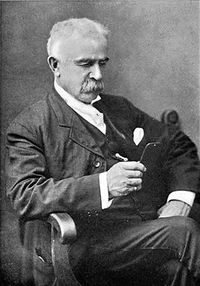

The Michigan Relics remained a topic of discussion for many years because, as many academics had assumed, the archaeological forgeries did not go away after being assessed in the 1890s. Rather, Scotford, who had moved to the Detroit area, persisted through the turn of the twentieth century and even assembled a team to help him promote the Michigan Relics, which were still being "discovered" into the 1910s. The key individual that became involved with James O. Scotford was Daniel E. Soper. Soper was the Secretary of State for the State of Michigan in 1891 under Governor Edwin Winans. Soper was, however, accused of embezzlement and was forced to resign after a single year in office.[14] Soper had previously amassed a large collection of genuine artifacts of North American mounds. In 1907, Soper began his relationship with Scotford in relation to the Michigan Relics.

Soper had a questionable past. Besides being a disgraced former Secretary of State, Soper had fled the state of Michigan to escape any backlash or repercussions from the embezzlement allegations. He moved to Arizona, where he attempted to fool local archaeologists by planting and then "discovering" Native American artifacts. The scholars in Arizona were not easily fooled and exposed Soper as a fraud. He then returned to Michigan, fleeing the trouble he had gotten into in Arizona. With a not-so-clean past, Soper became a main promoter of the relics that were continually being uncovered throughout Michigan. Soper's motivations for becoming involved was likely entirely financial. Scotford was still making money off the fraudulent relics and Soper, with his unscrupulous past, saw an opportunity to join him in making money.

As Scotford and Soper persisted with the Michigan Relics, so too did academics and the media. In 1907, the Detroit News called the frauds “the most colossal hoax of a century." The News, in addition to reviving some of the original observations about the pieces, pointed out that no discoveries had been made without James Scotford or Daniel Soper.[16] This public deconstruction of the Michigan Relics as frauds silenced Scotford and Soper for a few years, but by 1911 they were back at it.

Perhaps the biggest supporter of Scotford and Soper was James Savage. Savage was pastor of the Most Holy Trinity Catholic Church and dean of the Western Detroit Diocese. Soper, who had a genuine collection of Native American artifacts that he had collected for several decades, grew into a firm believer that the Michigan Relics were genuine. Soper and Scotford took advantage of Savage's interest and sold him a large collection of the archaeological forgeries. Savage joined Soper in excavating and discovering more artifacts. Savage believed in several different explanations for the artifacts' presence in Michigan. First, he believed that Pre-Columbian Norsemen created the artifacts, then attributed their origins to the Lost Tribes of Israel, and eventually tied them to a colony of ancient Jewish settlers, who he said were killed by Native Americans. Genuine archaeology does not support any of the claims. Savage simply used the religious inscriptions on the fake relics to determine their origins.

Another proponent of the Michigan Relics was Rudolph Etzenhouser, who had joined Scotford, Soper, and Savage around this time as well. Etzenhouser was a traveling elder of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. He saw them as historical evidence for the historicity of the Book of Mormon. Etzenhouser even published a book of his collection of the Michigan Relics, in which he gives great credit and admiration to Daniel Soper for his "moving spirit in the investigation of these prehistoric relics of Michigan."[17]

In 1911, James Scotford's stepdaughter Etta Riley signed an affidavit that she saw her stepfather making the relics and had interacted with Scotford, Soper, and Savage regarding the validity of them. Scotford and Soper reportedly threatened her life when she questioned the fraudulent relics.[18] While Scotford never confessed to the hoax, his unending involvement with the relics and because no artifacts were ever found without his knowledge or presence, indicates that Scotford is the most likely perpetrator of the fraudulent archaeology. Both Scotford and Soper continued their work on the hoax until their deaths in the 1920s. Put simply, Scotford was the craftsman and Soper was the salesman in the great scheme of the Michigan Relics. Because of the vast number of objects produced, the relics did not die with their perpetrators. James Savage and Rudolph Etzenhouser were likely victims of Scotford and Soper's hoax and were probably used for their position in religion to add validity to the already-debunked yet long-lasting hoax. Savage died in 1927 and bequeathed his vast collection of the Michigan Relics to the University of Notre Dame.[19]

The 1960s to Today

In 1960, while proselytizing in South Bend, Indiana at the University of Notre Dame, two missionaries of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints came across James Savage's collection of the Michigan Relics. They wrote back to Milton R. Hunter, president of the New World Archaeological Foundation, the research institute of the Mormon Church. Hunter's research involved the historicity of the Book of Mormon through archaeological evidence. In 1962, Hunter visited Notre Dame to view the Savage collection, which the University subsequently gave him. Following his success at Notre Dame, Hunter contacted the son of Daniel Soper, Ellis Clarke Soper, who had inherited his father's collection. Ellis Soper originally lent Hunter a few pieces, but eventually gave him the entire collection. Hunter's diligence in his research and collection brought most of the Michigan Relics together.[21]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints invests greatly in attempts to prove the historical legitimacy of the Book of Mormon, often through archaeology. Hunter spent many years researching the Michigan Relics in attempts to prove their legitimacy. While Rudolph Etzenhouser had attempted to make this connection earlier in the twentieth century, Hunter was more committed to the cause and spent the rest of his life working at it. Hunter was, however, among the only interested parties in the Mormon Church. Most other officials, including president David McKay, trusted prior assessments and evaluations that deemed them archaeological forgeries. Hunter persisted, just as Scotford and Soper did, in ignoring basic facts about the Michigan Relics and published extensively on them. Eventually Hunter connected the "Michigan Mound Builders" who made the relics to the Nephites from the Book of Mormon. This conclusion perpetuated the mound builder myth that already existed in pseudoarchaeology. Before his death in 1975, Hunter left his vast collection of Michigan Relics to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.[22]

The Church kept the relics in its Salt Lake City, Utah museum for decades before taking any action with the vast collection. Though Hunter deemed them real, along with several other individuals, the Church never presented them as genuine. In 2001, the Mormon Church had the collection examined once and for all by Professor Richard Stamps, an anthropologist from Oakland University. He found that the Michigan Relics were not genuine archaeological artifacts.[24] With that finding, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints donated the collection of 797 objects to the Michigan History Museum in Lansing, Michigan in 2003.[25] The Michigan History Museum developed an exhibition surrounding the Michigan Relics titled "Digging Up Controversy: The Michigan Relics" which was shown in the fall and winter of 2003. Dr. John Halsey, Michigan state archaeologist, noted in a 2017 documentary film Hoax or History: The Michigan Relics, "Nobody ever fessed up. Without having any of the perpetrators admit it, there is this lingering doubt. A lot of people take that as evidence that it really wasn't a fraud. So people expect that there is some kind of resolution, and the lack of a resolution leaves a doubt."[26]

While the Michigan Relics have been discredited, debunked, denounced, and exposed on numerous occasions, there are many individuals who continue to use the pseudoarchaeological objects in a narrative that supports their beliefs. There are countless websites and small private publications that fail to call the Michigan Relics frauds, including a 1996 publication titled "Mystic Michigan" by Mark Jager, which outlines 49 sites and artifacts relating to the state of Michigan and refers to the Michigan Relics as the "Ancient Michigan Tablets." Jager gives a brief history of the "tablets," which is not entirely correct, and notes a "controversy" over the "validity" of them. Jager cites "archaeological researcher" Lois Benedict of Boon, Michigan, who concluded that the "tablets," which she deemd were a mixture of genuine and fake, did contain religious inscriptions.[27]

Pseudoarchaeology

With the rhetoric in which they were originally presented, the Michigan Relics attempted to support pseduoarchaeological narratives, primarily pre-Columbian contact. With their hieroglyphic inscriptions, the discoveries attempted to support the idea that the state of Michigan and North American in general were inhabited, or visited, by European peoples before the existence of Native American tribes in the region and before the popularly-believed discovery of the North American continent by Europeans. In 1891, when a portion of the Michigan Relics were presented to the University of Michigan, the "jumble" of inscriptions was explained as having its origins in a colony occupied by peoples from Egypt, Phoenicia, and Assyria. Another explanation as to why they were found in Michigan is that the relics made their way from the Tigris and Euphrates, across the Atlantic, through the St. Lawrence River, and into the Great Lakes and Michigan.[29]

The inscriptions found on the clay and copper discoveries were considered similar in appearance to the the Egyptian, Greek, Assyrian, Phoenician, and Hebrew alphabets, which was considered proof of an advanced "composite" civilization that existed in the region before or besides Native Americans. The inscriptions were also considered religious in nature and therefore were seen as proof that the advanced civilization had knowledge of the Old Testament.[30] This rhetoric surrounding pre-Columbian contact has major problems because it is ethnocentric and racist at its core and degrades Native Americans. The Michigan Relics and the rhetoric behind them also subverts real archaeology by presenting fraudulent artifacts as real with a supposed archaeological and historical background, and eventually discrediting archaeologists and scholars in their stances against the validity of the relics.

In an 1892 publication The Mound-Builders: Their Works and Relics, author Rev. Stephen D. Peet, Ph.D., notes that "During this time there have been many discoveries; consequently many changes of thought. These discoveries and changes have had regard first to the Mound-builders' problem." He noted that many discoveries had added increased evidence of pre-Columbian contact.[31] The Michigan Relics are among the discoveries that promoted the idea of pre-Columbian contact and dangerously perpetuated the myth of the mound-builders. Arguments used by adherents to the idea include: (1) Native Americans were too primitive, barbaric, and uncivilized to have built the mounds; (2) the mounds and artifacts are ancient and pre-date Native Americans; and (3) the languages on tablets and other artifacts tie the mounds and artifacts to European, African, and Asian civilizations. The perpetrators and supporters of the Michigan Relics used all of these arguments to prove that their objects supported pre-Columbian contact.

The Michigan Relics did not attempt to use genuine artifacts of the mound-builders to promote pre-Columbian contact. Scotford and Soper had little care in perpetuate such an idea, rather they simply cared about making money off the fraudulent artifacts. However, their greed and disregard for legitimate archaeology add to the pseudoarchaeological idea of pre-Columbian contact and the myth of the mound-builders. Despite countless academics - archaeologists, linguists, and historians - disproving the legitimacy of the Michigan Relics through the host of reasons mentioned throughout, the perpetrators persisted for their own personal gain which in turn perpetuated pseudoarchaeologists and their ideas of pre-Columbian contact.

The attempts of Milton R. Hunter and others involved with the New World Archaeological Foundation and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints continued the perpetuation of the Michigan Relics after they had been out of the spotlight. By attempting to use the archaeological fakes in religious archaeology to prove the Book of Mormon, Hunter continued the racist and ethnocentric rhetoric of the idea of pre-Columbian contact. Hunter was also anti-archaeology and anti-scientific in his efforts because of the blatant disregard for the countless scholars who had discredited the Michigan Relics as legitimate.

References

- ↑ Kelsey, Francis W., "Archaeological Forgeries from Michigan." American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Jan. - Mar., 1908), 50-51. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/659777.pdf

- ↑ Ashurst-McGee, Mark. "Mormonism's Encounter with the Michigan Relics," BYU Studies, vol. 40, no. 3 (2001), 175. https://byustudies.byu.edu/content/mormonisms-encounter-with-michigan-relics

- ↑ Ashurst-McGee, Mark. "Mormonism's Encounter with the Michigan Relics," BYU Studies, vol. 40, no. 3 (2001), 178. https://byustudies.byu.edu/content/mormonisms-encounter-with-michigan-relics

- ↑ Kelsey, Francis W., "Archaeological Forgeries from Michigan." American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Jan. - Mar., 1908), 48-59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/659777.pdf

- ↑ Ashurst-McGee, Mark. "Mormonism's Encounter with the Michigan Relics," BYU Studies, vol. 40, no. 3 (2001), 177-178. https://byustudies.byu.edu/content/mormonisms-encounter-with-michigan-relics

- ↑ Young, Lisa, "Michigan's Mystery Relics." Archaeology, Vol. 57, No. 3 (May/June 2004), p. 53. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41779755?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

- ↑ Ashurst-McGee, Mark. "Mormonism's Encounter with the Michigan Relics," BYU Studies, vol. 40, no. 3 (2001), 178. https://byustudies.byu.edu/content/mormonisms-encounter-with-michigan-relics

- ↑ Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan. https://www.flickr.com/photos/79736948@N02/26005683552/in/dateposted-public/

- ↑ Kelsey, Francis W., "Archaeological Forgeries from Michigan." American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Jan. - Mar., 1908), 49-51. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/659777.pdf

- ↑ Ashurst-McGee, Mark. "Mormonism's Encounter with the Michigan Relics," BYU Studies, vol. 40, no. 3 (2001), 179. https://byustudies.byu.edu/content/mormonisms-encounter-with-michigan-relics

- ↑ Kelsey, Francis W., "Archaeological Forgeries from Michigan." American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Jan. - Mar., 1908), 48-59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/659777.pdf

- ↑ Kelsey, Francis W., "Archaeological Forgeries from Michigan." American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Jan. - Mar., 1908), 48-59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/659777.pdf

- ↑ Ashurst-McGee, Mark. "Mormonism's Encounter with the Michigan Relics," BYU Studies, vol. 40, no. 3 (2001), 181. https://byustudies.byu.edu/content/mormonisms-encounter-with-michigan-relics

- ↑ "List of Michigan Secretaries of State." Michigan Department of State. Accessed November 22, 2017. http://www.michigan.gov/sos/0,4670,7-127-1640_9105_61239---,00.html.

- ↑ Etzenhouser, Rudolph, Engravings of Prehistoric Specimins, from Michigan, U.S.A. (Detroit, Mich.: John Bornman & Son Printers, 1910). https://hdl.handle.net/2027/njp.32101078162284

- ↑ “Daniel E. Soper in a Fake Relic Business,” Detroit News, November 14, 1907, p. 2, col. 3

- ↑ Etzenhouser, Rudolph, Engravings of Prehistoric Specimens, from Michigan, U.S.A. (Detroit, Mich.: John Bornman & Son Printers, 1910). https://hdl.handle.net/2027/njp.32101078162284

- ↑ Ashurst-McGee, Mark. "Mormonism's Encounter with the Michigan Relics," BYU Studies, vol. 40, no. 3 (2001), 187-188. https://byustudies.byu.edu/content/mormonisms-encounter-with-michigan-relics

- ↑ Ashurst-McGee, Mark. "Mormonism's Encounter with the Michigan Relics," BYU Studies, vol. 40, no. 3 (2001), 195. https://byustudies.byu.edu/content/mormonisms-encounter-with-michigan-relics

- ↑ Ashurst-McGee, Mark. "Mormonism's Encounter with the Michigan Relics," BYU Studies, vol. 40, no. 3 (2001), 174. https://byustudies.byu.edu/content/mormonisms-encounter-with-michigan-relics

- ↑ Ashurst-McGee, Mark. "Mormonism's Encounter with the Michigan Relics," BYU Studies, vol. 40, no. 3 (2001), 196. https://byustudies.byu.edu/content/mormonisms-encounter-with-michigan-relics

- ↑ Ashurst-McGee, Mark. "Mormonism's Encounter with the Michigan Relics," BYU Studies, vol. 40, no. 3 (2001), 196-197. https://byustudies.byu.edu/content/mormonisms-encounter-with-michigan-relics

- ↑ Kelsey, Francis W., "Archaeological Forgeries from Michigan." American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Jan. - Mar., 1908), 50. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/659777.pdf

- ↑ Stamps, Richard B., "Tools Leave Marks: Material Analysis of the Scotford-Soper-Savage Michigan Relics." BYU Studies, vol. 40, no. 3 (2001), 210-238. https://www.jstor.org/stable/i40117989.

- ↑ "Mormon church donates debunked artifacts to Michigan museum," Associated Press, October 27, 2003.

- ↑ Dr. John Halsey, Hoax or History: The Michigan Relics, 2017. https://vimeo.com/ondemand/102838/60903399

- ↑ Jager, Mark. Mystic Michigan, (Cadillac, Michigan: Zomsa Publications, 1996), 52.

- ↑ Ashurst-McGee, Mark. "Mormonism's Encounter with the Michigan Relics," BYU Studies, vol. 40, no. 3 (2001), 182. https://byustudies.byu.edu/content/mormonisms-encounter-with-michigan-relics

- ↑ Kelsey, Francis W., "Archaeological Forgeries from Michigan." American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Jan. - Mar., 1908), 53. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/659777.pdf

- ↑ Talmage, James Edward. "The Michigan Relics: A Story of Forgery and Deception." Deseret Museum Bulletin, No. 2 (1911), 6-8. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.32044043476324

- ↑ Peet, Stephen D., The Mound-Builders: Their Works and Relics (Chicago, Ill.: Office of the American Antiquarian, 1892), ix-xi. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.hn4t2y