Beardmore Relics

By Elijah Wakefield

Beardmore Relics

The weapons unquestionably are genuine Norse relics of about A.D. 1000. [1]

What are the Beardmore Relics

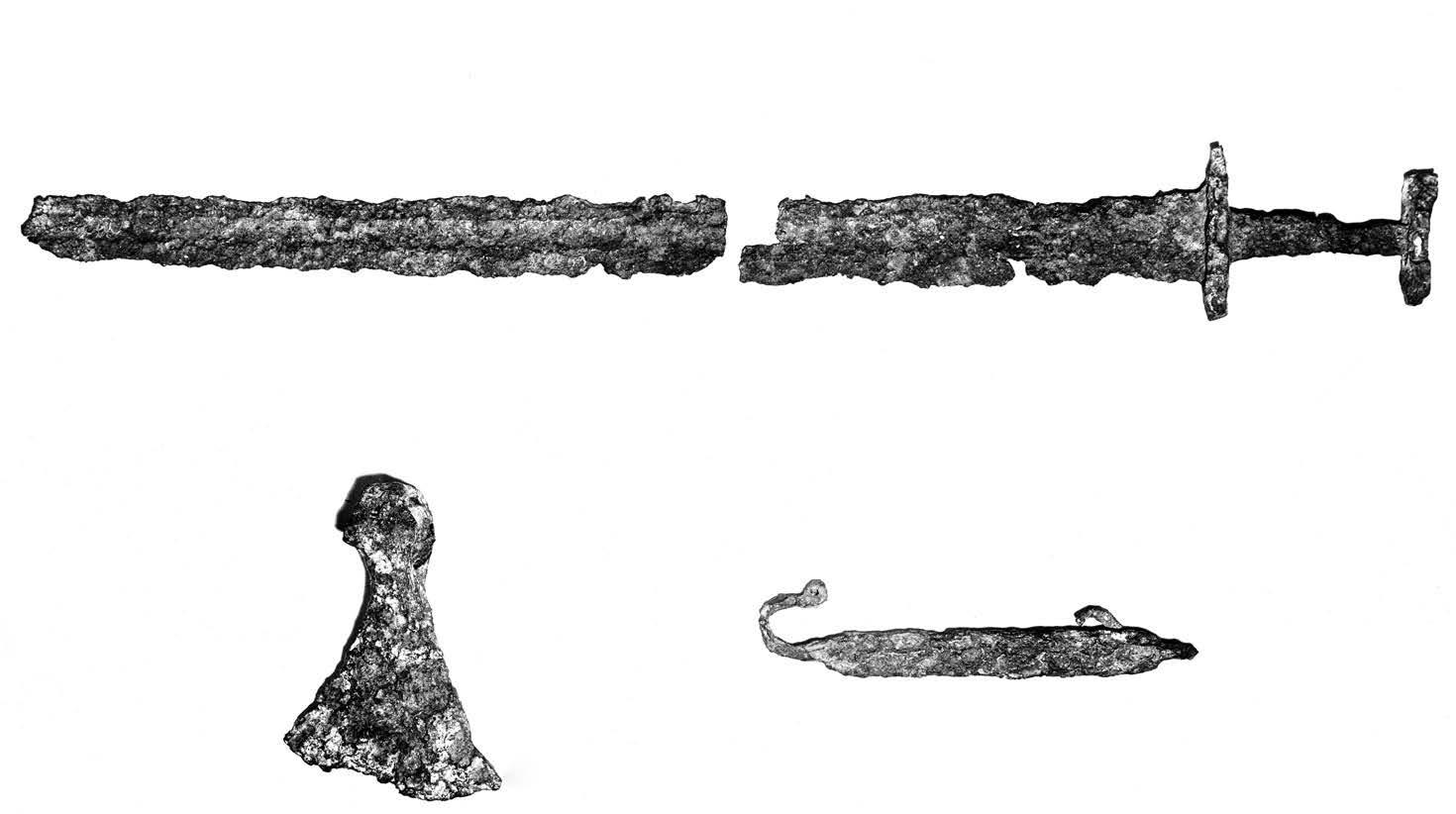

There has been controversy over the existence of the Beardmore Relics, a collection of Viking Age artifacts found near Beardmore, Ontario, Canada, in the 1930s. The collection consists of a Viking Age sword, an axe head, and an item of unknown purpose (perhaps part of a shield). Although the authenticity of the fragments is not generally disputed, the "discovery" is commonly regarded as a hoax.[2] The Royal Ontario Museum purchased the relics from the man credited with finding them in the 1930s. For about twenty years, the relics were conspicuously displayed by the museum; however, in 1956–1957, the museum was forced to take them down following a public inquiry. Around this time, the son of the supposed discoverer confessed that his father had planted the relics. [2]

[3]

[3]

Discovery

James Edward Dodd

In the early 1930s James Edward Dodd, a prospector and conductor from Port Arthur, Ontario alleged to have discovered Viking weapons which later became known as the Beardmore Relics and is the man who is credited with the discovery of the Beardmore Relics. His adventure began when he came across rusty iron relics on a mining claim near Beardmore, northeast of Nipigon, which he brought home and sold to the Royal Ontario Museum a few years later for $500 which would be about $7,000 today. [4] There was much speculation, accounts, and stories regarding the validity of these relics, however, one of the most incriminating testimonies was one in which Dodd's adopted son came forward and and stated that Dodd actually found the relics in the basement of their home in Port Arthur, Ontario and later transported them to Beardmore and laid them in a spot that he had been digging previously. Several months later, he came forward with the same relics which he hid and claimed that he had uncovered them. Eventually, a man came forward with allegations that would further corroborate the nature of the relics as being a hoax. A man by the name of J.M Hanson claimed Dodd was given the relics as security on a loan of $25 by a Norwegian named John Bloch. The relics were then left in the basement of a Port Arthur house that James Dodd later rented. However, it is said that J.M Hanson wasn't completely sure if the relics he saw were the same as the ones displayed in the Royal Ontario Museum. [4]

Pseudoarchaeological Significance

In 1936, Toronto's Royal Ontario Museum purchased Norse artifacts from prospector Eddy Dodd, who said he'd found them during a mining expedition in Beardmore, Ontario. As proof that the Vikings had been in the northern part of the province, the museum displayed the relics. [5] The relics led to a sense of nationalistic pride for northern Ontario because at the time the relics offered alluring evidence that at least one Viking, possibly more, travelled into the heart of the continent 400 years before Columbus. [6] For almost 20 years the relics were prominently displayed in a glass encasement in such a fashion that if you visited, it'd be difficult for your to miss them. In 1956, great controversy arose about the relics and they were removed from display for decades. Although the majority of people agreed that the artifacts were authentic, the crux of the people's concerns was whether the relics had actually been discovered or if they had been planted in Northern Ontario. Most people believed that the relics were planted and consequentially, the Royal Ontario Museum fell under scrutiny and suspicions of whether or not one of their "greatest discoveries" was a deliberate hoax. Dr. Charles Trick Currelly was the first director of the Royal Ontario Museum who once admitted "Any success I have had as an archaeologist has been due to the most amazing blind luck". This quote attributed to Currelly in retrospect could be interpreted as him having a care-free attitude and allowing artifacts to be exhibited without sufficient examination. A few years before the artifacts were placed on display, a geologist from the provincial government, Dr. E.M. Burwash, told Currelly rumors of Norse artifacts around Port Arthur. After Currelly sent out a letter to the geologist that received no reply, he started to believe it to be improbable to find authentic Viking artifacts, though he desired for a long time to find some to put on display for the Royal Ontario Museum. However, after receiving a sketch of the objects, Currelly thought that the artifacts were authentic and wrote to James Edward Dodd stating that "If you can give or obtain proof that these were not planted there by some Norwegian or Swede in recent years, we will be willing to give you a very good price for them.” When the Currelly and Dodd met, Currelly was shown a sword split in two pieces, an axe head, and a rattle. Confident in his ability to identify forgeries, Currelly deduced that the relics were real, of Nordic origin and that they dated to around 1000 A.D. Dodd swore that he had discovered the relics and not planted them and with Currelly searching for over 30 years for relics, he was pleased to purchase them from Dodd. Interestingly, a highly publicized controversy erupted before the relics were even shown publicly, with accusers saying that they had been planted by Dodd. As the curator (Currelly) noted, the authenticity of the artifacts was not in doubt, only their location of discovery. After the relics were approved to be displayed, they remained there for 18 years and garnered lots of attention for the Royal Ontario Museum. Even those of Nordic lineage traveled to the museum and saw the relics as proof that their ancestors predated Columbus in coming to the Americas. Later an expert with the federal government argued that a nine-century-old iron implement would have been completely corroded by the soil conditions around Beardmore given the corrosion seen at other nearby mine sites. Others spoke up making claims that weapons of that style can only be found in Eastern Norway. One of the most notable critics (the first to call the relics an outright fraud) was an anthropologist by the name of Edward Carpenter who went as far as to pen a book review with Toronto telegram calling the relics "Ontario’s most famous archaeological frauds." [6]

The disappearance & reappearance of the relics

On December 4, 1956 the relics were removed from the case on display and replaced with a small card that stated "temporarily removed." A few weeks later the case too had mysteriously vanished. Initially officials of the Royal Ontario Museum deemed the Beardmore Relics to be one of their greatest historical finds of all time, but today it is considered one of their greatest embarrassments.[7] Many years later however, the Beardmore relics returned to the Royal Ontario Museum for public display in the 1990s.[6]

The Beardmore Relics as a Hoax

In spite of the lack of absolute proof in either direction, the weapons received a place of honor in the Museum's galleries for many years. Publications of all kinds (including textbooks) as documentation that the Norsemen at one time entered into the upper Great Lakes area around 1000 A.D. [1] On November 30, 1956 a retired prospector by the name Carey Marshman Brooks volunteered to give his testimony in Fort William and himself called the Beardmore Relics a deliberate hoax. Although there were many accounts that swore that James Edward Dodd fabricated the discovery of the Beardmore Relics, it is not understood why Dodd would have carried out such a hoax, seeing that he did not seek after much publicity or profit. It was only through a schoolteacher named O.C. Elliot, that the Royal Ontario Museum found out about the existence of the relics. As of the present day, the Beardmore Relics are said to remain in the storage of the Royal Ontario Museum within the category of uncertain history. The evidence for or against the discovery ultimately depends too much on the circumstances for assertions to be made that it is an absolute hoax, but popular opinion leans more toward the relics as being a hoax. [1]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 https://nipigonmuseumtheblog.blogspot.com/2011/09/beardmore-relics-hoax-or-history-how.html.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 “Beardmore Relics.” The Argumentative Archaeologist, https://www.andytheargumentativearchaeologist.com/beardmore-relics.html.

- ↑ https://www.tbnewswatch.com/local-news/the-beardmore-saga-how-the-discovery-of-viking-relics-in-northern-ontario-rewrote-history-7-photos-1058679.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 https://www.sootoday.com/columns/remember-this/did-vikings-roam-the-great-lakes-some-once-thought-so-1999982.

- ↑ https://quillandquire.com/review/beardmore-the-viking-hoax-that-rewrote-history/.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 https://torontoist.com/2014/11/historicist-an-authentic-viking-hoax/.

- ↑ https://archive.macleans.ca/article/1957/4/13/was-our-biggest-historical-find-our-biggest-hoax.