Bat Creek Inscription

Bat Creek Inscription Stone

by Amina Johnson

What is the Site/Artifact?

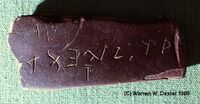

The Bat Creek Stone was excavated in 1889 by a man named John Emmert, he worked for the Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology. The Smithsonian was conducting a Mound Survey Project, the director being Cyrus Thomas. Emmert excavated three mounds located at the confluence of Little Tennessee River and Bat Creek. The Bat Creek Stone was found beneath the smallest mound in the group, Mound 3. It was reported that the mound was “composed throughout, except about the skeletons at the bottom, of heard red clay, without any indication of stratification.” Also,” nine skeletons were found lying on the original surface of the group, surrounded by dark-colored earth.” Excavator Emmert said, “ two copper bracelets, an engraved stone, a small frill fossil, a copper bead, a bone implement, and some small pieces of polished wood soft and colored green by contact with the copper bracelets.”were found under the skull and mandible of the skeleton and the “engraved tone lay partially under the back part of the skull.”

Interpretations of the Stone

Initial interpretation

According to Cyrus Thomas, director of the project, the stones inscription was initially thought to be letters of the Cherokee alphabet, invented by Sequoyah around 1821. This conclusion was not based on similarity to the Cherokee syllabary, but the find’s location near the heart of historical Cherokee territory. This did not challenge the assumption that Columbus was first.

Second interpretation

The stone remained in the Smithsonian Museum from the time it was shipped in 1889 until 1962. No one ever paid the stone any mind until 1964, two individuals by the names of Henriette Mertz and Corey Ayoob. They discovered a drawing of the stone published in 1894 by the Smithsonian. They noticed that the stone was upside down. She published the discovery in her book The Wine Dark Sea: Homer’s Heroic Epic of the North Atlantic. A professor by the name of Joseph B. Mahan, Jr, Director of Education and Research at the Columbus, Georgia, Museum of Art and Crafts had read her book and noticed that is the stone was turned right side up, the inscription was Canaanite. The Sequence of lettering was: LYHWD

In 1970, Professor Cyrus Gordon, professor of Mediterranean Studies at Brandeis University, a fanatic of Pre-Columbian contacts between the old and new world, and a Semitic languages scholar, confirmed that it was Semitic, more specifically Paleo-Hebrew of the first or second century A.D. He discovered that the letters meant “For Judea” of alternatively “for the Judeans”. The five letters to the left of the comma-shaped word divider read, from right to left, LYHWD; “for Judea.” The broken letter on the far left is consistent with mem, which would make it read LYHWD[M], meaning “For the Judeans.”

Paleo Hebrew is the Phoenician-Like Alphabet that was used to write Hebrew and other Semitic Languages in First Temple Times ( before 586 B.C.). When the Jewish Exiles returned from Babylon, beginning in 538 B.C., they replaced these old letters with the Aramaic-based, square-Hebrew alphabet that is used today. However, paleo-Hebrew continued to be the preferred script for coin legends whenever Judea threw off foreign domination. The paleo-Hebrew script is not known to be used until 135 A.D., the era of the Bar Kochba revolt against Rome (132 to 135). This is the date when Rome finally suppressed the second Jewish Revolt. Gordon asserted that the letters on the stone resembled those on the coins of the First (66-70 A.D.)and Second Jewish Revolt against Rome. Therefore, he dated the inscription to that approximate period.

Special Notes

It was acknowledged by Gordon that three signs “are not in the Canaanite system. ”McCulloh also noted that several of the letters are not perfect Paleo-Hebrew.

The Pseudoarcheological Narrative

There is a controversial narrative that took the forefront of academic debate that proposes that people from Africa, Asia, and Europe or Oceania visited and interacted with indigenous people of American before Christopher Columbus's first Voyage. This is called the Pre-Columbian theory. There is not enough sufficient evidence for this theory to take on mainstream acknowledgment by scientists and scholars. The only evidence of Pre-Columbian contact is that the Norse people during the 10th century led to the colonization of Greenland and L’Anse Aux Meadows in Newfoundland. All other claims of Pre-Columbian contact are considered to be Pseudoarchaeological.

The reason behind this theory is that there is no biblical explanation about where indigenous came from. Many people reasoned that they were not indigenous and derived from some other group of people that made contact with America before Columbus. This would explain their presence in America. Many also came up with idea that the structures, tools, earthworks, artifacts, and language hadn’t come from the indigenous people because they weren’t intelligent enough. Their culture and physical manifestations had to have come from some other group of people that came far before Columbus. As a result, the debate and hunt for evidence of Pre-Columbian contact proliferated throughout society.

If indeed the Bat Creek Stone was Paleo-Hebrew, it would then provide evidence of Pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact. During that time period, Gordon was quoted saying that “Various pieces of evidence point in the direction of migrations [to North America] from the Mediterranean in Roman times. The cornerstone of this reconstruction is at present the Bat Creek inscription because it was found in unimpeachable archaeologists working for the prestigious Smithsonian Institute. This follows the belief that there was actually Pre-Columbian contact of the New World far before Columbus.

In 1988, J. Huston McCulloh, an Ohio State University economics professor confirmed Gordon's assertions. McCulloh published a paper on the Stone and the brass bracelets that were found in the mound in Tennessee Anthropologist. He noted that the results of a radiocarbon assay on copper-stained wood fragments found in the burial site as the stone belong somewhere between 32 A.D and 769 A.D. Since the Cherokee Alphabet was not made until the 1820s, the “Cherokee” inscription could not have been made before this period. This range was consistent with Cyrus Gordon’s dating.

The Deconstruction of the Pseudoarchaeological Narrative

The psuedoarchaeological narrative associated with the Bat Creek Inscription is that the inscription is Paleo-Hebrew, dating back to the First and Second Jewish Revolt against Rome. If that is true, then the Stone is proof that there was Pre-Columbian contact with America. In the years to come, the Bat Creek Inscription was scrutinized heavily by various scholars claiming that it was a fraud. There are multiple sources of evidence presented and argued of this.

Theory 1

The first is that the Bat Creek Inscription appears in the General History, Cyclopedia, and Dictionary of Freemasonry. Professor Emeritus Frank Moore Cross studied General History and observes that it is copied from the coin script of the First Jewish Revolt against Rome. The inscription is the General History translates to “Holiness to the Lord”. This expression appears throughout the bible multiple times. The word “Lord” was used as a substitute for YHWH, meaning Yahweh, which is the divine lord. It is argued that the General History would have been available to the person who forged the Bat Creek Inscription.

Theory 2

Secondly, there was correspondence between John Emmert, the mound excavator, and Cyrus Thomas, the Smithsonian’s Director of the Mound Survey, that was quite concerning. First, we must provide a backstory about John Emmert. Cyrus Thomas had dismissed Emmert one on occasion because of his drinking problems that he admitted to. Emmert wanted his job back but was still on leave for nearly a year. Although he was not officially hired, Thomas still hired Emmert in 1889 to do some additional work.

In the Mound survey files, there is a letter written by John Emmert to President Grove Cleveland in 1888 asking for reemployment with the Smithsonian Institution Bureau of Ethnology. The senator at the time, Harris, wrote a note to Thomas’s supervisor stating that he would be delighted to rehire Emmert “if consistent with public interest.” That statement alone implicated that there was an agenda with the rehiring of Emmert. Thomas had declined the Senators request but Emmert was still rehired between December 19, 1888, and early February 1889. This action also could lead skeptics to believe that there was political pressure to hire Emmert, but why?

There was a letter written December 19, 1888, by Emmert to Thomas stating “ I have just received and read your Burial Mounds, and I certainly agree with you that the Cherokees were Mound Builders. In fact, there is not a doubt in my mind about it.” That is coincidental because the Emmert just happen to find a mound with a stone tablet with what is believed to be Cherokee letters a year later.

After Emmert started his fieldwork again, the first letter he wrote to Thomas was on February 15, 1889. Emmert reported in a letter to Thomas that “ I will prove everything just as found.” The wording of Emmert’s letter is a tad bit sketchy. Could he have known that people would be skeptical of his finding, so he felt the need to reassure Thomas that everything will be “just as found.”?

On February 25, 1889, just ten days later after the first letter, Emmert included a drawing of the stone in a letter to Thomas stating “I think it is a good idea to look into everything near here that we might find something else like the stone, or that might have some connection with it.” The letter closes with “please inform me what the inscription on the stone is.” The verbiage from the letter suggests that the stone is a fraud. Scholars believe that Emmert wanted to get into Thomas’s good graces by making a significant discovery that would ground his employment at the Smithsonian.

Theory 3

Thirdly, the Smithsonian officially made a statement concluding that the Bat Creek Inscription is a fake. They stated that: “While recognizing that a diversity of opinion continues to circulate around the authenticity of the Bat Creek Stone, the curators in the Department of Anthropology at the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian. Institution, believe that the inscriptions on the artifact are forgeries and that the artifact is fake. This opinion is widely shared by other professional archaeologists as represented in the article by Robert Mainfort and Mary Kwas ‘The Bat Creek Stone Revisited: A Fraud Exposed’, American Antiquity 2004. Along with other known fraudulent artifacts, we retain it in our collections as part of the cultural history of archaeological frauds, which were known to be quite popular in the second half of the 19th century.”

Conclusions

The Bat Creek Inscription is a stone that was found beneath the smallest mound in the group, Mound 3. The Inscription was believed to be written in Cherokee. Years and years later, the inscription became under scrutiny because someone identified that the stone was actually upside down. After that, the stone was deemed to be paleo-Hebrew by a professor named Cyrus Gordon. The controversy behind the stone is that if it is Paleo-Hebrew then it would prove evidence of pre-Columbian contact. There is no definitive evidence that the Bat Creek Stone inscription is fraudulent but there are factors that call into question its legitimacy. The first factor was that the inscription was eerily similar to the text found in General History with the exception of a few letters. The next is the validity of the excavator himself. The fieldworker by the name of John Emmert was previously fired from the Smithsonian for his drinking issues. He was then rehired with my political pressure from Senator Harris at the time to be rehired. Emmert was rehired, to the dismay of Director Cyrus Thomas. Correspondence between Emmert and Thomas heavily suggests a need to please the director, which is suspicious. Perhaps Emmert was trying to ensure his permanent employment at the Smithsonian by making an important finding. The next piece of evidence is that the Smithsonian actually stated that the stone was a fake. There are many motives at play to believe the stone was actually Cherokee or even Paleo-Hebrew.

References

- ↑ Additional digging uncovers source of Bat Creek hoax. Home. (2014, May). Retrieved December 10, 2021, from https://www.ohiohistory.org/learn/collections/archaeology/archaeology-blog/2014/may-2014/additional-digging-uncovers-source-of-bat-creek-ho.

- ↑ Mainfort, R. C., & Kwas, M. L. (1993). THE BAT CREEK FRAD: AFINAL STATEMENT. The Bat Creek Fraud: A final statement. Retrieved December 10, 2021, from http://www.ramtops.co.uk/bat2.html.

- ↑ Mainfort, R. C., & Kwas, M. L. (2004). The Bat Creek Stone Revisited: A Fraud Exposed. Institutional database of Staff Publications Tennessee Division of Archaeology . Retrieved December 10, 2021, from https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/environment/archaeology/documents/staffpubs/arch_Mainfort%20and%20Kwas%202004.pdf.

- ↑ McCulloh, J. H. (2010, September). The Bat Creek Stone. Bat Creek Inscription. Retrieved December 10, 2021, from https://www.asc.ohio-state.edu/mcculloch.2/arch/batcrk.html.

- ↑ McCulloch, J. H. (2015, November 5). The Bat Creek inscription: Did judean refugees escape to Tennessee? The BAS Library. Retrieved December 10, 2021, from https://www.baslibrary.org/biblical-archaeology-review/19/4/9?ip_login_no_cache=%99%A7%E7to%5C%17%CF.

- ↑ North, G. (2016, April). Facts, rhetoric, and innuendo in ... - ronpaulcurriculum.com. Ronpaulcurriculum.com. Retrieved December 10, 2021, from https://www.ronpaulcurriculum.com/BatCreekDebate.pdf.

- ↑ Report of Archaeopetrography investigation. (2010, July 14). American Petrographic Services, inc.. American Petrographic Services, Inc. Retrieved December 10, 2021, from http://www.ampetrographic.com/files/BatCreekStone.pdf.