Baalbek Megaliths: Difference between revisions

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

== Site Description == | == Site Description == | ||

=== The Quarry === | === The Quarry === | ||

The quarry at Baalbek, sometimes referred to as Ḥajjar al-Ḥibla (meaning “The Stone of the Pregnant Woman”), has been the subject of study since antiquity. Recently, more focused research has started, with the German expedition in 2004 being one of the most in-depth. The quarry is the site of all the megalithic stones used at Baalbek, including the Trilithon that makes up the podium of the Temple of Jupiter. It lies about 800 m southeast of the temple complex and consists of four “extraction areas” that provided the megalithic stones of the podium and those left in the ground. Some of the caves left behind from extractions have since been used as burial sites, most likely during the Byzantine era. <ref | The quarry at Baalbek, sometimes referred to as Ḥajjar al-Ḥibla (meaning “The Stone of the Pregnant Woman”), has been the subject of study since antiquity. Recently, more focused research has started, with the German expedition in 2004 being one of the most in-depth. The quarry is the site of all the megalithic stones used at Baalbek, including the Trilithon that makes up the podium of the Temple of Jupiter. It lies about 800 m southeast of the temple complex and consists of four “extraction areas” that provided the megalithic stones of the podium and those left in the ground. Some of the caves left behind from extractions have since been used as burial sites, most likely during the Byzantine era. <ref>Massih, Jeanine Abdul, 2015, The Megalithic Quarry of Baalbek: Sector III the Megaliths of Ḥajjar al-Ḥibla. Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology & Heritage Studies 3(4): 313–329,https://www-jstor-org.proxy2.cl.msu.edu/stable/pdf/10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.3.4.0313.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A5437b5c0e894d03abde95061d9356024</ref> | ||

==== The Stone of the Pregnant Woman ==== | ==== The Stone of the Pregnant Woman ==== | ||

The Stone of the Pregnant Woman, also referred to as Ḥajjar al-Ḥibla, gives its name to the quarry site of Baalbek. It sits in the extraction area labeled “Area III”, and is 4.2 m x 4.5 m x 21 m in size. The megalith itself shows evidence of tool marks and holes that were most likely used for transportation of the stone from its extraction cave. There is evidence on three of the four sides of working on the stone to smooth the facades.<ref | The Stone of the Pregnant Woman, also referred to as Ḥajjar al-Ḥibla, gives its name to the quarry site of Baalbek. It sits in the extraction area labeled “Area III”, and is 4.2 m x 4.5 m x 21 m in size. The megalith itself shows evidence of tool marks and holes that were most likely used for transportation of the stone from its extraction cave. There is evidence on three of the four sides of working on the stone to smooth the facades.<ref>Massih, Jeanine Abdul, 2015, The Megalithic Quarry of Baalbek: Sector III the Megaliths of Ḥajjar al-Ḥibla. Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology & Heritage Studies 3(4): 313–329,https://www-jstor-org.proxy2.cl.msu.edu/stable/pdf/10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.3.4.0313.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A5437b5c0e894d03abde95061d9356024</ref>[[File:Two_Megaliths.png|thumb|The Stone of the Pregnant Woman on the left and the Area III megalith on the right.<ref>Massih, Jeanine Abdul, 2015, The Megalithic Quarry of Baalbek: Sector III the Megaliths of Ḥajjar al-Ḥibla. Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology & Heritage Studies 3(4): 313–329,https://www-jstor-org.proxy2.cl.msu.edu/stable/pdf/10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.3.4.0313.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A5437b5c0e894d03abde95061d9356024</ref>]] | ||

==== Area IV Megalith ==== | ==== Area IV Megalith ==== | ||

The megalith at the Area IV extraction area is the second-largest megalith found in the quarry. Its dimensions of 4.6 m x 4.8-5.0 m x 20 m make it larger than the Stone of the Pregnant Woman. The megalith was completely buried in mining debris and was uncovered in the 1970s. It is considered to be a higher quality stone than that of the Stone of the Pregnant Woman and may have been intended to have been part of the podium of the Temple of Jupiter. <ref | The megalith at the Area IV extraction area is the second-largest megalith found in the quarry. Its dimensions of 4.6 m x 4.8-5.0 m x 20 m make it larger than the Stone of the Pregnant Woman. The megalith was completely buried in mining debris and was uncovered in the 1970s. It is considered to be a higher quality stone than that of the Stone of the Pregnant Woman and may have been intended to have been part of the podium of the Temple of Jupiter. <ref>Massih, Jeanine Abdul, 2015, The Megalithic Quarry of Baalbek: Sector III the Megaliths of Ḥajjar al-Ḥibla. Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology & Heritage Studies 3(4): 313–329,https://www-jstor-org.proxy2.cl.msu.edu/stable/pdf/10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.3.4.0313.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A5437b5c0e894d03abde95061d9356024</ref> | ||

==== Area III Megalith ==== | ==== Area III Megalith ==== | ||

The megalith at the Area III extraction area is the most recent discovery at the site, as it was uncovered during excavations in 2014. The megalith was uncovered below ground level just to the north of the Stone of the Pregnant Woman, almost underneath it. It measures 5.6 m x 6.1 m x 19.6 m and has several imperfections on some of its facades, including some horizontal cracks and the formation of an imperfection known as karst.<ref | The megalith at the Area III extraction area is the most recent discovery at the site, as it was uncovered during excavations in 2014. The megalith was uncovered below ground level just to the north of the Stone of the Pregnant Woman, almost underneath it. It measures 5.6 m x 6.1 m x 19.6 m and has several imperfections on some of its facades, including some horizontal cracks and the formation of an imperfection known as karst.<ref>Massih, Jeanine Abdul, 2015, The Megalithic Quarry of Baalbek: Sector III the Megaliths of Ḥajjar al-Ḥibla. Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology & Heritage Studies 3(4): 313–329,https://www-jstor-org.proxy2.cl.msu.edu/stable/pdf/10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.3.4.0313.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A5437b5c0e894d03abde95061d9356024</ref> | ||

=== The Temple of Jupiter Platform === | === The Temple of Jupiter Platform === | ||

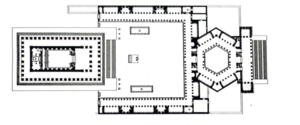

[[File:Screen_Shot_2019-11-24_at_2.06.00_PM.png|thumb|Architectual plan of the entire Sanctuary of Jupiter at Baalbek. The podium of the temple is depicted on the far left of the plan.]] The podium of the Temple of Jupiter is constructed of three megalithic stones known as the Trilithon. These stones are considered to be some of the largest stones used in construction in history. Each of the stones is 4 m x 4 m x 20 m, and weigh about 800 tons.<ref name="Upton, Dell"/> The information on the construction of the podium and thus the temple is foggy. It is relatively considered that construction began in the first century BCE, and finished in the third century CE (Reconstructing Baalbek). | [[File:Screen_Shot_2019-11-24_at_2.06.00_PM.png|thumb|Architectual plan of the entire Sanctuary of Jupiter at Baalbek. The podium of the temple is depicted on the far left of the plan.]] The podium of the Temple of Jupiter is constructed of three megalithic stones known as the Trilithon. These stones are considered to be some of the largest stones used in construction in history. Each of the stones is 4 m x 4 m x 20 m, and weigh about 800 tons.<ref name="Upton, Dell"/> The information on the construction of the podium and thus the temple is foggy. It is relatively considered that construction began in the first century BCE, and finished in the third century CE (Reconstructing Baalbek). | ||

Revision as of 00:25, 6 December 2019

The Baalbek Megaliths are large megalithic stones located at the site of Baalbek in the Baalbek Valley in Lebanon. The site includes a quarry with large megaliths still left in the ground, the most famous being that of the Stone of the Pregnant Woman, along with a Roman temple complex. The complex itself, sometimes referred to as Qalaa, consists of the Temples of Jupiter, Bacchus, and Venus, along with a large sanctuary to Jupiter as well. The podium of the Temple of Jupiter is made of three large megalithic stones known as the Trilithon.[1][2] (Monumentality)

Site History

Baalbek has been continuously inhabited since the Neolithic Period, due to its ideal geography. It has been proposed that it was the site of religious/cultic activities during the Iron Age. There is evidence that the site was built on during this period, found in excavations under the Roman courtyard, and potentially a terrace for an old temple that was covered by the Romans through the Trilithon(Monumentality). The site of Baalbek has been the subject of debate for many centuries. However, what is seen on the site nowadays is generally considered to have been built by the Romans between the 1st and 3rd centuries CE (Starting from Baalbek) (Monumentality). Baalbek was first excavated in 1898-1903 by a German expedition. The site was ruined, and many expeditions, including some done by the French and Lebanese, reconstructed some of the temple structures during the 1930s, ’50s, and ’60s. The names of the Roman temples at the site, being the temples of Jupiter, Bacchus, and Venus, were given without evidence of being named as such. The site has been studied since the mid-18th century. The antiquarian Robert Wood wrote The Ruins of Balbec, Otherwise Heliopolis in Coelosyria in 1757, which started the main archaeological interest in the site.[2] The study of the site was interrupted due to the Lebanese civil war from 1975-1990. German expeditions continue to be done on the site, with research focuses on the quarry of Baalbek and the podium of the Temple of Jupiter.[3]Current research is being done into the site through joint Lebanese and German expeditions to try and construct a chronology of the building of the site (Monumentality).

Site Description

The Quarry

The quarry at Baalbek, sometimes referred to as Ḥajjar al-Ḥibla (meaning “The Stone of the Pregnant Woman”), has been the subject of study since antiquity. Recently, more focused research has started, with the German expedition in 2004 being one of the most in-depth. The quarry is the site of all the megalithic stones used at Baalbek, including the Trilithon that makes up the podium of the Temple of Jupiter. It lies about 800 m southeast of the temple complex and consists of four “extraction areas” that provided the megalithic stones of the podium and those left in the ground. Some of the caves left behind from extractions have since been used as burial sites, most likely during the Byzantine era. [4]

The Stone of the Pregnant Woman

The Stone of the Pregnant Woman, also referred to as Ḥajjar al-Ḥibla, gives its name to the quarry site of Baalbek. It sits in the extraction area labeled “Area III”, and is 4.2 m x 4.5 m x 21 m in size. The megalith itself shows evidence of tool marks and holes that were most likely used for transportation of the stone from its extraction cave. There is evidence on three of the four sides of working on the stone to smooth the facades.[5]

Area IV Megalith

The megalith at the Area IV extraction area is the second-largest megalith found in the quarry. Its dimensions of 4.6 m x 4.8-5.0 m x 20 m make it larger than the Stone of the Pregnant Woman. The megalith was completely buried in mining debris and was uncovered in the 1970s. It is considered to be a higher quality stone than that of the Stone of the Pregnant Woman and may have been intended to have been part of the podium of the Temple of Jupiter. [7]

Area III Megalith

The megalith at the Area III extraction area is the most recent discovery at the site, as it was uncovered during excavations in 2014. The megalith was uncovered below ground level just to the north of the Stone of the Pregnant Woman, almost underneath it. It measures 5.6 m x 6.1 m x 19.6 m and has several imperfections on some of its facades, including some horizontal cracks and the formation of an imperfection known as karst.[8]

The Temple of Jupiter Platform

The podium of the Temple of Jupiter is constructed of three megalithic stones known as the Trilithon. These stones are considered to be some of the largest stones used in construction in history. Each of the stones is 4 m x 4 m x 20 m, and weigh about 800 tons.[2] The information on the construction of the podium and thus the temple is foggy. It is relatively considered that construction began in the first century BCE, and finished in the third century CE (Reconstructing Baalbek).

Pesudoarchaeological Claims

Religious Claims

Due to the nature of the uncertainty of the building of the Baalbek temple complex and the megalithic size of the stones, the site has garnered pseudoarchaeological claims on its origin and purpose.

Solomon

Most of the claims that have their footing in religion are focused on the Trilithon of the Temple of Jupiter podium. These claims ignore the classical architecture seen at the site in favor of the idea of the podium having Biblical origins. The site was often identified in antiquity as the site of a palace built by King Solomon for the Queen of Sheba. Local legends also claimed that genies were responsible for helping Solomon build the podium because no human workers could have been responsible for the moving of such megalithic stones. This section of the story also explains the Stone of the Pregnant Woman, by claiming that the genies left the stone in the ground as a strike against Solomon for making them work. During the 19th century, it was common for literature to reference Baalbek as such for those who wished to prove the historicity of the Bible. David Urquhart’s work, The Lebanon: A History and a Diary, claimed that the Trilithon had been built in three stages. Two of these stages was before the great Biblical flood, by the claimed exceptional race of men who died during the aforementioned flood. The last stage was completed by Solomon (Starting at Baalbek). Muslim sources follow the same narrative, including that it was the palace of Abraham, or that it was the castle of Solomon built to honor Abraham. There are also others that claim the city is related to the Biblical “Baalath.” (History of Baalbek)

Other Religious Claims

There are many other religious claims laid on the site, varying greatly across the board. One tells that the podium of Baalbek was the foundation of the Tower of Babel and being built by Nimrod. In a related story from an Arabic manuscript, Baalbek was built under the order of Nimrod when he ruled Lebanon after the flood (History of Baalbek). Istifan Al-Duwayhi has been quoted saying that the site was built but Cain in a “fit of raving madness," and that it was given to his son and then populated by giants after the flood (History of Baalbek). Another recounts that the site was built by giants who worshipped “the Sun-God” (History of Baalbek).

Ancient Aliens

In episode 3, season 3 of Ancient Aliens, the show references the theory of Baalbek being thousands of years older than its actual age. The show also claims that the podium and courtyard of the site was a landing pad for ancient alien spacecrafts, and that it is sacred due to the fact that it was the first landing site. Its basis for the site being built by aliens is based mainly on the idea that the site could not have been built by humans due to the fact that they did not have the technology (Ancient Aliens).

Nationalism

The site has been the subject of nationalitstic claims, both in antiquity and in the present. During the early years of exploration and recording done by European powers in the 17th and 18th centuries, the site was used as a way to justify a claim on Lebanon. Since the site was built by Rome, which was seen as the foundation of the West, they claimed the site to have a profoundly European origin, disconnecting it from its history in the region. Kaiser Wilhelm II held a deep fascination with the site after visiting it during a tour of the Holy Land in 1898, claiming that Baalbek was the ancestral homeland of the Holy Roman Empire, and thus of Germany. Upton Dell has stated on the subject: “it represented European culture implanted autocratically in the East through imperial might…” (Starting at Baalbek). The Ottoman Sultan Abdulhamid II, the site allowed for an Ottoman claim on part of Rome’s impact in the East. (Starting at Baalbek). Lebanese excavations were done on the site during the 19th century to try and gain a glimpse into the site’s supposed pre-Classical past. These were done out of Lebanese nationalist claims to try and connect the site with early Christianity (Starting at Baalbek).

Other Pseudoarchaeological Claims

There are many claims to be found about Baalbek on independent websites, most of which are not scholarly based. One such claim connects stonework at Baalbek with the work done at Giza in Egypt. The claim states that the stonework is similar and that the boat burials found at Giza are made of cedarwood, which is plentiful at Baalbek and the region surrounding. The claim also discusses there is a numerical interest in the site:

“This very specific separation of both longitudes and latitudes between the two sites has a secondary significance in that the angle created is 51° 51', which is the same angle as that of the exterior faces of the [G]reat [P]yramid at Giza.” (Forgotten Stones Ancient Origins)

Most claims about the site claim that the Romans were not involved in the construction of the site. Usually, the claims cite that the masonry of the Trilithon is not Roman in nature, compared to the stones that are used to build atop it. Graham Hancock has been an advocate for the belief that the stones are not the work of the Romans. On his personal blog he states:

“I believe these huge megaliths long predate the construction of the Temple of Jupiter and are likely to be 12,000 or more years old — contemporaneous with the megalithic site of Gobekli Tepe in Turkey. I suggest we are looking at the handiwork of the survivors of a lost civilisation, that the Romans built their Temple of Jupiter on a pre-existing, 12,000-years-old megalithic foundation… ”

This idea that the stones of Trilithon and the stones of the quarry have become popular in internet communities. Often, people connect the quarry of Gobekli Tepe to that of the quarry of Baalbek, referencing the stones left behind there (cite the ancient origins story). While claims about the quarry are not as common as those related to podium of the Temple, they still exist on independent websites. Graham Hancock believes that the stones in the quarry are not the work of Romans. He claims that the stones in the quarry were left there due to the fact that the Romans did not even know they existed. He raises the question of why the stones weren’t moved and states:

“It’s really puzzling that they didn’t do so and therefore the fact that these gigantic, almost finished blocks remain in the quarry and were never sliced up into smaller blocks and used in the general construction of the Temple of Jupiter, suggests to me very strongly that the Romans did not even know they were there. Most probably they had been buried under many metres of sediment for many thousands of years when the Romans appeared on the scene.”

Disproving the Pseudoarchaeological Claims

One of the many questions asked in the pseudoarchaeological claims of the site is the megaliths left in the quarry. The question raised is that they were left due to the Romans not knowing they were even there. There are a few points to disprove this claim. Firstly, one of the most recently discovered stones, the Area III megalith, had two long cracks on its facade(Megalith Quarry). It was most likely left behind due to this fact. Another factor in this suggests that the construction of the complex at Baalbek was halted suddenly and that the stones were left behind in the quarry as a response (Megalith Quarry). Another theory is brought up by Jeanine Abdul Massih:

“Three megaliths were abandoned in the quarry, probably due to modifications of the monumental building project. The megaliths were used generally in the foundation of the Temple of Jupiter and more precisely for the construction of its podium. A reduction in the dimensions of the temple could have led to an interruption in megalith extraction, but it also could have been related to an economic crisis and a shortfall in the funds needed to complete the project according to its original plan”

(Megalithic Quarry)

In terms of the theory of the Romans not having the ability to move the stones, there is evidence at the megaliths left in the quarry that helps disprove this. The megalith at Area III has square and round holes dug into the surface, which archaeologists have posited are connected to extraction and movement techniques. There is also extensive trench work evident on the site that has been connected to the extraction and movement of the blocks (Megalith Quarry). This corresponds to a theory posited that large rollers were used to haul the stones and that the paved roads from the quarry were made specifically to allow the stones to either move on flat land or downhill. There is also a theory given by J.P. Adams that states that a system of pulley stones and manpower could lift the stones, which corresponds to the square and round holes left in the blocks (Megalith Quarry). This disproves the theory posed by Ancient Aliens as well. The claim of the site of being non-Roman has been argued against due to the classical Roman architecture of the site, and that the work on the site (including the extraction of the megaliths) would have needed to have been very well funded to be successful (Megalith Quarry; Reconstructing Baalbek). In terms of the claim that the trilithon is not Roman in architecture, it could be due to the fact that the site was not completed (Starting from Baalbek). Graham Hancock’s theories have very clear pseudoarchaeological narratives due to his heavy belief in the existence of Atlantis and the evidence of his work is clearly focused around hyperdiffusionism (Christopher Hale 242-245). The claims that Baalbek is the site of Solomon’s palace, that it is related to the Biblical site of “Baalath”, or that it was inhabited by giants is an example of Biblical literalism, given that all evidence found at the site points towards Roman origins.

- ↑ Massih, Jeanine Abdul, 2015, The Megalithic Quarry of Baalbek: Sector III the Megaliths of Ḥajjar al-Ḥibla. Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology & Heritage Studies 3(4): 313–329,https://www-jstor-org.proxy2.cl.msu.edu/stable/pdf/10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.3.4.0313.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A5437b5c0e894d03abde95061d9356024

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Upton, Dell

- ↑ Massih, Jeanine Abdul, 2015, The Megalithic Quarry of Baalbek: Sector III the Megaliths of Ḥajjar al-Ḥibla. Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology & Heritage Studies 3(4): 313–329,https://www-jstor-org.proxy2.cl.msu.edu/stable/pdf/10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.3.4.0313.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A5437b5c0e894d03abde95061d9356024

- ↑ Massih, Jeanine Abdul, 2015, The Megalithic Quarry of Baalbek: Sector III the Megaliths of Ḥajjar al-Ḥibla. Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology & Heritage Studies 3(4): 313–329,https://www-jstor-org.proxy2.cl.msu.edu/stable/pdf/10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.3.4.0313.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A5437b5c0e894d03abde95061d9356024

- ↑ Massih, Jeanine Abdul, 2015, The Megalithic Quarry of Baalbek: Sector III the Megaliths of Ḥajjar al-Ḥibla. Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology & Heritage Studies 3(4): 313–329,https://www-jstor-org.proxy2.cl.msu.edu/stable/pdf/10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.3.4.0313.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A5437b5c0e894d03abde95061d9356024

- ↑ Massih, Jeanine Abdul, 2015, The Megalithic Quarry of Baalbek: Sector III the Megaliths of Ḥajjar al-Ḥibla. Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology & Heritage Studies 3(4): 313–329,https://www-jstor-org.proxy2.cl.msu.edu/stable/pdf/10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.3.4.0313.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A5437b5c0e894d03abde95061d9356024

- ↑ Massih, Jeanine Abdul, 2015, The Megalithic Quarry of Baalbek: Sector III the Megaliths of Ḥajjar al-Ḥibla. Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology & Heritage Studies 3(4): 313–329,https://www-jstor-org.proxy2.cl.msu.edu/stable/pdf/10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.3.4.0313.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A5437b5c0e894d03abde95061d9356024

- ↑ Massih, Jeanine Abdul, 2015, The Megalithic Quarry of Baalbek: Sector III the Megaliths of Ḥajjar al-Ḥibla. Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology & Heritage Studies 3(4): 313–329,https://www-jstor-org.proxy2.cl.msu.edu/stable/pdf/10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.3.4.0313.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A5437b5c0e894d03abde95061d9356024